In February, while on voyange south from Philadelphia to Atreco, the Gill had picked up 25 survivors of the torpedoed bulk-ore carrier Marore.

“he released and launched a life-raft from a sinking and burning ship and maneuvered it through a pool of burning oil to clear water by swimming under water, coming up only to breathe. Although he had incurred severe burns about the face and arms in this action, he then guided four of his shipmates to the raft, and swam to and rescued two others who were injured and unable to help themselves.“

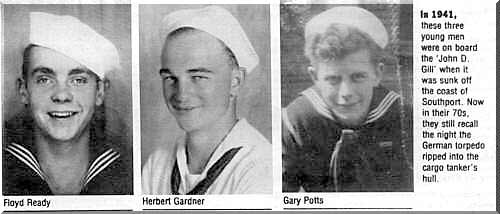

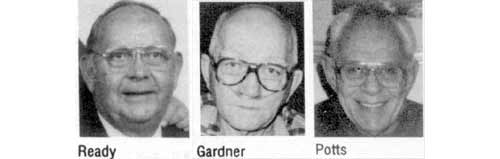

A Night to Remember: Survivors, town look back at WWII sinking of 'John D. Gill' (11)

25 miles off the Cape Fear coast. The torpedo from the German sub hit the tanker John D. Gill amidships, tearing the heavy metal plates of the hull like flower petals. A geyser of Texas crude erupted from the gash, forced out by pressure from the million gallons behind it. Within a minute, the slick had coated the sea. An instant later, the oil erupted in an inferno and 58 men began a desperate scramble for their lives. Only 26 of them made it, 52 years ago March 12. Eleven were brought into Southport to recuperate at Dosher Memorial Hospital. Of the 16 bodies also brought ashore, one, Catalino Tingzon, was buried in the town's Northwood Cemetery.

At 11 a.m. March 12, the Southport Historical Society will dedicate a monument to Tingzon and all the men of the Gill. The gray granite stone will sit in Riverfront Park, overlooking the horizon where the tanker burned and sank. On March 11, 1942, the Gill put into Charleston after planes spotted a submarine tailing it. At 12:45 p.m. the next day, having been given the all clear, it continued on its way to the Atlantic Refining Company's refinery in Philadelphia. About 10 that night, Herbert Gardner, 22, one of the wipers, was in the mess, having a cup of coffee and wondering aloud what he'd do if the

Gill was torpedoed. At 10:10 p.m., he got his answer.

"When it hit, it was like it picked the chair up and moved it out from under me," Mr. Gardner said. "We knew what had happened."

Outside, someone threw a life preserver into the widening oil slick. The preserver was equipped with a self-igniting carbide flare, which burst to life.

"When that happened.., we started burning," said Floyd Ready, one of the Navy Armed Guard assigned to the Gill. "That was West Texas crude; it had a very high gasoline content."

Mr. Ready and seaman Gary Potts had been hard asleep when the torpedo hit. They scrambled to the stern to get to their gun, a 5-51 breech-loader. All members of the gun crew made it to their post -- Mr. Ready, Mr. Potts, Seaman David M. Lunn, Seaman Asa Bob "Tex" Senter and their commander, Ensign Robert D. Hutchins. Newspaper reports of the day said the men stayed at their post for more than 15 minutes after the rest of the crew had abandoned ship.

"We really wanted to at least get one shot off," Mr. Potts said, "But the sub could have come 'up outside the fire and we wouldn't have seen it anyway. The fire was too bright."

But they stayed, squinting through the heat and flames into the darkness, swinging the barrel of the big gun back and forth. Finally, with the flames inching closer, the surface of the ammunition box began to bubble.

"When the paint started blistering on that-- ready box, Hutchins, our officer, said, 'Let's get the hell out of here,' "Mr. Ready said.

Their life raft in flames, the men jumped over the railing.

"We jumped right into the fire," Mr. Ready said. "We didn't have any choice,"

Mr. Potts didn't jump; he dove. "I used to dive off railroad bridges . .. and I wasn't thinking about the Navy telling me to jump feet first. I said the heck with the Navy and did what I thought best."

Had he jumped, he would have broken both legs on the hull of the capsized No. 4 lifeboat, which was tethered to the stern of the tanker below him. As it was, his toes clipped the lifeboat gunwales as he dove past.

Mr. Gardner had rushed to that same lifeboat, minutes earlier. But as he and several others tried to lower it, the boat suddenly dropped away beneath them, spilling two men into the water. Mr. Gardner and another crewman managed to grab a line and were left dangling.

Below them, the ship's massive screws were still churning. Mr. Gardner watched as the two men dumped from the lifeboat were pulled into the blades.

Desperately, he and the other man tried to get a better grip on the line and each other. But the other man was too weak to climb any further and Mr. Gardner couldn't hold him. Suddenly, he was alone, tethered to the hull of the burning ship.

"That's bothered me all my life," he said. When the screws stopped, he dropped into the water, next to the capsized lifeboat. One of the Filipino mess boys -- Mr. Gardner thinks it was Tingzon -- was sitting in the half-sunk lifeboat, soaked and frightened.

"He was scared so bad, he didn't know what to do," Mr. Gardner said. "I remember him saying, 'No. No. no.' '

Unable to help Tingzon and fearing for his own life, Mr. Gardner started to swim. Even wearing a cork life preserver, he managed to dive beneath the flames.

"When you're scared, you can do anything," he said.

There was no way to tell where the sea was on fire and where it wasn't.

"Every time I'd come up, I'd come up on fire," he said. "My head and my hands would be on fire." Finally, he came up clear of the oil and swam away from the ship. Mr. Potts had also gotten clear of the oil, amazingly, without getting burned.

Beyond them in the dark, men were climbing aboard a lone life raft.

When the ship was hit, Edwin F. Cheney Jr., the ship's 24-year-old quartermaster, had managed to drop the raft at the edge of the burning oil and push it beyond the fire by swimming under water.

Once clear of the ship, he started calling to survivors and hauling aboard those too weak to make it.

"He helped us get aboard and he was pretty badly burned himself," Mr. Ready said. "His ears and his arms were burned."

Most of the men had third-degree burns on their heads and arms. Mr. Garnder would later vomit for nearly two hours because his stomach was so full of seawater and oil.

During the night, Mr. Cheney and Mr. Potts pulled the Filipino cook, Benny, from the water. "He was burned so bad he was freezing to death," Mr. Potts said. So he gave the cook his life preserver, an act that would cost him dearly later.

The men quickly realized the heat from the fire was drawing them back toward the tanker, where they'd burn to death or get sucked down with the ship. Just as quickly, they discovered the oars were useless; there were no oarlocks.

So, bent double, their hands gripping the boards at the bottom of the raft, the men took turns being human oarlocks.

It worked. Slowly, the raft pulled free of the heat. Even though he'd had a life preserver as a buffer, Cheney's abdomen was black where the oars had pressed against him. Mr. Potts, who'd given up his life preserver, was injured internally.

For the rest of the night, the men clung to the raft, watching their ship die by inches. The fire was so bright, the smoke so thick, people watched it from shore the next day.

"It kept burning and burning and blowing up and blowing up... until it finally just literally blew itself to pieces," Mr. Ready said.

They watched the ammunition explode, including a round left in the gun that had been intended for the Germans.

At 7:05 a.m., the survivors were picked up by a Coast Guard cutter from the Southport Station, USCGC-186.

At 9 a.m., theJohn D. Gill sank. The survivors came ashore in Southport, a small fishing village where the most exciting thing to date had been when two convicts kidnapped a young couple and tried to escape through the Green Swamp in 1937.

Josephine Hickman, 80, was a volunteer Red Cross nurse at Dosher Memorial Hospital when the survivors were brought in. "We didn't think even half of them hardly could live," she said. "They were so burned, almost to a crisp, and covered with oil. Some of them were burned so bad that... the bandages were all over their heads. Only their mouths were open. You just fed them in between the bandages."

The hospital staff worked 20 hours straight tending to the men. There were only five trained nurses. The rest, like Mrs. Hickman, were Red Cross volunteers. "We'd barely gotten our training when this tanker was torpedoed offshore and here we were faced with this terrible tragedy," she said. "But we managed to save every one of them."

As the 11 survivors were being treated, the USCGC Agassiz and USCGC-4342 brought in 16 bodies. Joseph S. Laughlin, who was 15 and whose father was manager of the hospital, helped carry the dead. "They were burned so bad their flesh would come off in your hands," he said.

Among the dead was Tingzon, the young mess boy Mr. Gardner bad last seen sitting in the capsized lifeboat. When efforts to find Mr. Tingzon's family in the Phillipines failed, the people of Southport buried him in Northwood cemetery. According to the Morning Star April 12, 1942, the grave was covered with flowers.

In addition to the 11 who escaped with Mr. Cheney, 15 others escaped in a lifeboat and survived the sinking, including Capt. Allen D. Tucker.

A few weeks after the sinking, President Franklin D. Roosevelt awarded Mr. Cheney the war's first Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal for his heroism.

The submarine that sank the Gill, U-158, was sunk west of Bermuda on June 30, 1942. There were no survivors.